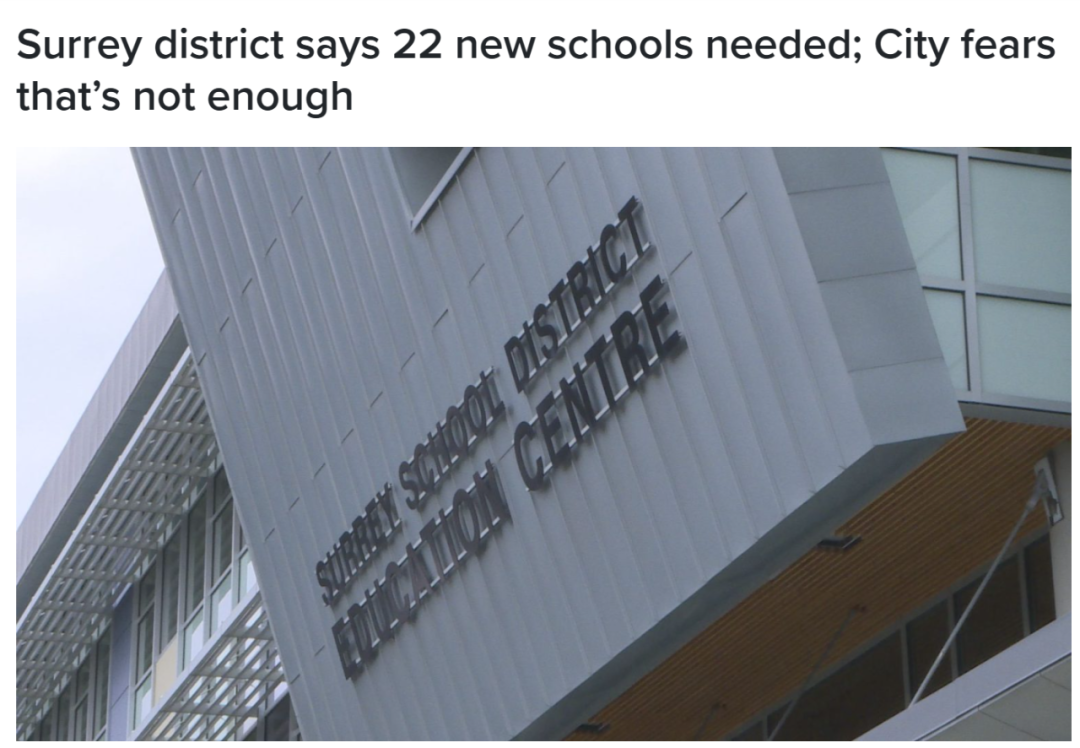

What is redshirting, and does it happen in Canada? (Part 2 of 2)

上周,大中报重点介绍了“红衫行为”这种美国教育现象:在美国,约有9%的5岁的儿童——大约十一个孩子当中的一个——被“红衫”了,也就是说,他们的父母要等孩子6岁时再给他们报名上幼儿园。到时候,这些孩子就会比自己的同班同学年纪大一些、身体高大一些,而且——从理论上讲——也更成熟一些。

Last week, Chinese News wrote about the American practice of redshirting, in which parents of an estimated nine percent of American five-year-olds – roughly child one in 11 – delay enrolling their kids in kindergarten, until they’re six – older, larger and, in theory, more mature than their peers.

多伦多大学安省教育学院(OISE)副教授琳达•卡梅伦不鼓励“红衫行为”,但她说,这一现象的延续不仅得力于希望子女能获得更多竞争优势的家长,而且,美国教师似乎也开始建议采用这种做法,原因在于其对学生考试成绩的显著影响。

Linda Cameron, an associate professor with the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE) discourages redshirting, but said it’s not only parents seeking a competitive edge who perpetuate it – American teachers appear to recommend the practice too, because of its apparent effects on test results.

与加拿大的公立学校系统(其强调实施与孩子年龄相适应的课程)不同,美国的公立学校系统是基于标准化考试的——即使在幼儿园里也是如此。

Unlike Canada’s public school system, which emphasizes age-appropriate curriculum, the American system is based on standardized testing, even in kindergarten.

卡梅伦女士说:“我们从相关的研究得知,‘红衫行为’所给予的优势只是短期的。他们上的年级越高,这一优势就越不明显,而且事实上,一些研究表明,这对孩子其实是不利的。”

“We know from research that redshirting only shows its advantages immediately,” Ms. Cameron said. “It falls off as you go up in grades, and in fact some research has said that that it actually disadvantages kids.”

虽然“红衫行为”在安省是不允许的,但Central Montessori Schools负责幼儿教育的副校长爱伊莎•艾哈迈德说,她见过一些父母因类似原因——即加快孩子的成长——决定给孩子报名上蒙台梭利课程,直到孩子6岁为止,届时,根据有关的省级法律规章,他们就必须报名上小学一年级。

While redshirting is not allowed in Ontario, Ayesha Ahmed, vice-principal for toddlers at Central Montessori Schools, has seen parents enroll their children in Montessori programs for similar reasons – to accelerate their kids’ development – until children are six years old, when provincial law requires them to be registered in first grade.

艾哈迈德女士表示,她的学生对上学的准备程度远远超过就读于公立学校的幼童。

Ms. Ahmed’s students are “more than better prepared” for school compared to their public counterparts, she said.

她说,孩子从18个月起就能受益于蒙台梭利式教育。“当他们读完幼童至6岁儿童的初级课程时,他们便已能够阅读和书写了,而公立学校的学生则可能要等到一年级才开始(学会阅读和书写)。”

Montessori education “benefits children from the age of 18 months,” she said. “By the time they graduate (from the initial programs for toddlers to six-year-olds) they are reading and writing, whereas perhaps public students in grade one just start that.”

提供蒙台梭利式课程的TMS学院的负责人格伦•泽德尔埃科博士称,蒙台梭利模式课程着重于建造“对事物的具体理解能力”的基础,并培养出为许多父母视为理所当然的行为,例如肢体动作技能(站立、行走等)和精细运动技能(使用自己的手指)。

Dr. Glenn Zederayko, Head of TMS School, which offers a Montessori program, said the Montessori curriculum emphasizes a foundation of “concretely understanding things,” and developing behaviour many parents and schools take for granted, such as gross motor skills (standing, walking, etc.) and fine motor skills (using their fingers).

他说:“如果做得好的话,学生就会领先一步,但这并非由于他们做得更多或更快的缘故,而是因为他们是以一种与其年龄相适应的方式接受教导的。”

“If it’s done well, students get a leg up, but it’s not because they do more, faster, it’s because they’re taught in an age-appropriate manner,” he said.

例如,上TMS幼儿课程的18个月大的孩子通过使用儿童游乐设施来提升自己的肢体动作技能,并通过一些简单的练习——如在收到不同尺寸的螺母和螺栓后,将其连接在一起——来锻炼自己的精细运动技能。

For example, the 18-month-old children in TMS’s toddler program develop gross motor skills by using playground equipment, and fine motor skills through simple exercises such as being given nuts and bolts of different sizes, then being asked to put them together.

泽德尔埃科博士说:“这些其实就是写字的一个前提。我们在培养他们的手部动作能力,以便让他们写得更好。他们可以在一个在他人看来比较幼小的年龄就开始手写字母。”

“That is actually a precursor to writing. We’re developing their hands so they can write better,” Dr. Zederayko said. “They begin to write cursive letters at what others would consider an early age.”

同样的,他说,在蒙台梭利式课程的模式下,为了达到语言教育的目的,教师会对不同的语言模式进行示范,而不是采用直接的教学方法。

Similarly, he said, Montessori programs teach language by having instructors model language patterns, instead of through direct instruction.

泽德尔埃科博士说:“一个孩子可能会用手指一指某个物体,他们想告诉我们,他们想要这种料子,或想在那个玩具站玩耍,或是想吃某一种东西,而老师就会说:‘嗨,约翰,你想要那个苹果吗?’接着你就会看到这个孩子在那里摇摇头。老师就会说:“‘哦,我想吃这个苹果,请递给我吧。’”

“A child might point at something, trying to tell us they want that material, or work at that station, or have that food, and the teachers will say, ‘oh, John would you like that apple?’ And you’ll see the kid shaking his head,” Dr. Zederayko said. The teacher responds, “‘Well, I would like that apple please.’”

他说:“这往往会显得十分偶然,因为这是一种互动,是一种对话,但我们正在向他们示范新的技能和新的表达方式。如果你看看我们这里的一个18个月大的孩子在两年后取得了怎样的进步,看起来是加快了进步速度,但这并非是被故意加速的。”

“All of this tends to appear very incidental, because it’s interaction, it’s conversation, it’s in whatever the routine is, but we’re introducing new skills and new language,” he said. “If you start looking at the results of an 18-month-old child after two years here, it looks accelerated, but it’s not intentionally accelerated.”

泽德尔埃科博士说,他曾遇到过用强硬手段迫使子女逐步提高考试成绩的家长。他将这种情况比喻成在没有充分准备的条件下进行马拉松长跑,并称其将带来同样令人不快的结果。

Dr. Zederayko said he’s met parents forcibly push their children to achieve increasingly higher test scores. He likened this to running a marathon without sufficient preparation, and said it leads to equally unhappy results.

他说:“有时候我遇见一些无法理解这个道理的家长。关键的不是加快步伐,而是要慢慢来,并且将注意力集中于那些往往被人认为是无形的、但却是很重要的东西。”

“Sometimes I meet parents who don’t get it,” he said. “It’s not about rushing, it’s about taking your time and focusing on the things that sometimes people don’t see as tangible, but are important.”

他说:“总体而言,在我们学校,学生的父母希望他们的孩子能够快乐,具备良好的综合素质,并且准备好应对这个被认为变化多端、高深莫测的世界。他们并没有督促自己的子女去学更多的东西或加快学习速度。”

“Overall, parents of our students want their children to be happy, well-rounded and prepared to cope in a world that is perceived as uncertain and changing,” he said. “They are NOT pushing their children to do more, faster.”

在2011年9月的一篇《纽约时报》社论中,《欢迎来到您孩子的大脑》一书的合著者桑德拉•阿莫特和王声宏表示,在美国,“红衫行为”最终会对孩子造成不利影响。

In a September 2011 New York Times editorial, Sam Wang and Sandra Aamodt, authors of “Welcome to Your Child’s Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College,” wrote that in the U.S., redshirting ultimately disadvantages children.

被“红衫”的孩子虽然一开始能得到比其他同学更高的测试分数,但王博士和阿莫特女士称,在一个有25名学生的班里,平均的改善水平相当于从班里的第13位升至第11位。等读完了小学,这种优势就已经消失殆尽。

While redshirted kids initially receive higher test scores than their peers, Dr. Wong and Ms. Aamodt wrote that in a class of 25, the average level of improvement is equal to a child going from 13th place to 11th. That advantage fades by the end of elementary school.

他们写道:“到了高中阶段,被‘红衫’了的孩子就不那么积极,而他们的表现也更差一些。到了成年期……他们的终生收入就会减少一年的收入。”

“In high school, redshirted children are less motivated and perform less well,” they wrote. “By adulthood… their lifetime earnings are reduced by one year.”

事实上,最能够得益于与同自己年龄不同的人上课的学生就是那些跳级的孩子:作者们写道,上高级课程的年幼学生更可能进入学位课程,甚至称自己拥有更多的积极情绪。

In fact, the students who benefit most from enrolling in classes with peers of a different age are children who skip a grade: the authors wrote that younger students in advanced classes are more likely to pursue degrees and even report more positive emotions.

该篇社论的作者们认为,这是因为,儿童得益于“接近自己能力极限”的学习。

The authors believe this is because children benefit from learning “close to the limits of their ability.”

社论写道:“确保学习效果最大化的关键,并非在于得到所有正确的答案,而在于答错后及时纠正。太低的错误率会使学习变得索然无味,而过高的错误率则(使学生)缺乏收益感。”

“Learning is maximized not by getting all the answers right, but by making errors and correcting them quickly,” they wrote. “Too low an error rate becomes boring, while too high an error rate is unrewarding.”